This article is no longer actively maintained. While it remains accessible for reference, exercise caution as the information within may be outdated. Use it judiciously and consider verifying its content in light of the latest developments.

-----

Why does it take five years on average in Europe to get a Minimum Efficiency Performance Standard (MEPS) approved? If we include a few years to get a MEPS on the Ecodesign work program, and a few years after publication before the regulation enters into force, we easily end up with ten years from conception to market. Do other regions do better? Do you have benchmarks for the Americas, Asia or Africa? And are we working as fast as we can, or should we do better?

This interesting question generated a lot of insightful comments. The general consensus from LE members is that ten years in Europe does indeed seem a very long time, but is probably necessary due to the complexity of the large number of countries and the coordination required. It was also pointed out that starting from a green field is always a long process. It firstly involves raising the awareness of all national actors before being able to push this agenda as a political priority. But a long time span isn’t limited to Europe: in Brazil the mandatory MEPS for industrial motors took 14 years.

At the other end of the scale, the first MEPS in Tunisia for refrigerators took only three years, and included running a pilot voluntary phase, laboratory construction, and training of all stakeholders. Full-scale implementation took another two years. One respondent gave China the prize for speed, but added that “they don’t seem to worry too much about what industry thinks, and to date haven’t been overly diligent in enforcement activity.”

Here is a summary of the replies from the discussion:

The EU MEPS process is complex and takes time

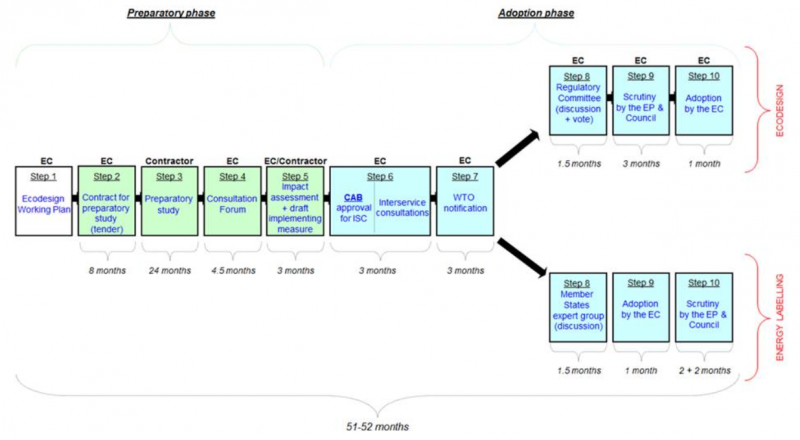

The long timespan is linked with the complexity and ambition of the EU process (see diagram below). The EU requires a lot of consultation. This takes place in a consultation forum, the Commission’s inter-service cabinet, a Regulatory Committee, the European Council, and the European Parliament, all of which takes time. Then the technical study itself takes two years as it is a highly involved piece of work that addresses many factors beyond just energy efficiency.

Moreover, typically the EU process involves considering Ecodesign measures for a whole swath of sub-products under one banner. For example, water heaters covered all types (gas, electric, oil, storage, instantaneous, solar, heat pump and biomass). Dedicated test procedures often need to be developed to handle this complexity.

Essentially the scope of work and consultative process in Europe are more in-depth than in other regions. The nearest parallel is the USA, where they also take their time but usually regulate any one product faster. This is partly because the DOE separates the test procedure development from the regulatory development process. It’s also because the scope in terms of products is narrower and is limited to energy in use rather than all the other product lifecycles and impacts.

The current review of the Ecodesign and labelling directives (http://www.energylabelevaluation.eu/eu/home/welcome) is considering remedial options, but even if it is not possible to shorten the time of regulatory development it is possible to ameliorate some of the negative effects by applying learning curve projections to the proposed efficiency thresholds.

The situation in Latin America

A member in Latin America suggests that the process in this region is influenced by a variety of factors such as the maturity of the policy makers, level of manufacturers’ technology, energy environment (energy crisis, rationing), consumer awareness, and laboratory infrastructure. The result is that sometimes the process to implement a MEPS can be longer than ten years!

The mandatory MEPS for industrial motors took 14 years. It was the first important process developed with a wide range of stakeholders led by an energy efficiency agent. The lessons learned with this case have reduced the time to implement MEPS to other equipment.

The recent mandatory MEPS for distribution transformers took almost six years between the creation of a work group and the regulation coming into force. Based on these experiences, new processes for implementing MEPS should take less than five years.

In Mexico the general regulatory environment is different. As Mexico is in NAFTA, the American rules are normally applied after a delay of a few years. Therefore the time to implement MEPS is shorter than other Latin American countries. However, the real issue is the enforcement of regulation, which can take more than five years.

Energy Star in the U.S. and Canada

The American view is to inform consumers of energy efficiency metrics on appliances through Energy Star ratings (kWh/year consumption patterns) of a wide assortment of electrical appliances. The idea is that consumers will make rational choices to reduce energy use by favoring high-efficiency appliances over those that have lower efficiency profiles.

In the US it seems that a legislative measure or policy that directly requires a minimum efficiency performance standard does not exist. For example, LEED standards for buildings are not legally enforceable. If a builder meets the standard they can market the certification level achieved – a sort of ‘negative reinforcement’ of performance standards for buildings design.

In Canada there are about 30 products that have MEPS in the national energy conservation law and Energy Star is the labeling program to pull the market toward higher efficiency.

Meanwhile in Israel …

...the methodology seems to be simpler. Performance measurement is generally put into standards which are not binding. The EE regulator reviews various performance demands worldwide and then makes a determination which is promulgated as a regulation. This process can take some time – generally not less than 1-2 years. The regulation prohibits imports of the appliances which do not meet these performance standards/regulations, so the inefficient equipment cannot enter the country. The regulation prohibits sale of non-compliant equipment/appliances. However, it gives a grace period for the market to sell off inventory.

Issues with the laboratory infrastructure

One of the main problems with MEPS that members reported is the laboratory infrastructure required. This does not exist in most countries, which are equipped to test equipment for safety but not for performance. Some countries like Vietnam take shortcuts and accept tests performed abroad by laboratories that are accredited. But this means that you need to be sure that the testing standard applied is the good one (North America, Europe and Asia use different standards).

No easy answer

Finally, one member recounted his experience of making a project for CLASP, which demonstrated that even for simple equipment like AC units there is no simple way to compare the testing results between jurisdictions except by developing a transfer function. Then the MEPS level has to be decided by benchmarking to other jurisdictions, or like Europe by doing background studies to adjust the MEPS base on life cycle cost optimization for society. However, this is not generally done from the user point of view because of price distortion embedded in rates.

Thanks to comments and answers received from Hugh Falkner, Paul Waide, Glycon Garcia, Bob Aceti, Zev Gross and Pierre Baillargeon.

Comments

0 comments

Please sign in to leave a comment.